Other US financial giants such as AIG and Citigroup stood on the verge of collapse. General Motors and Chrysler filed for Chapter 11 protection. A credit freeze spread worldwide, with Iceland, Hungary and other European markets in crisis. Global trade shrank immediately. Japan was hit hard, recording GDP growth of minus 18 percent on an annualized basis for the first quarter of 2009.

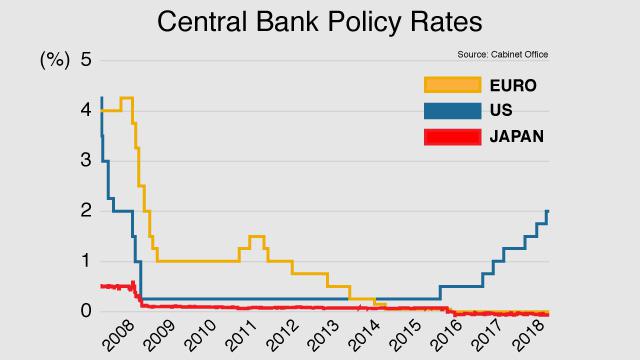

Financial authorities went into action. US Federal Reserve chief Ben Bernanke moved to pump liquidity into the markets by introducing a near-zero interest rate. The policy was unprecedented in the history of the Fed. The Bank of Japan and the European Central Bank eventually followed suit. Developed and emerging countries worked together to confront the global financial crisis by promising 5 trillion dollars' worth of economic stimulus, and doubling the resources of the International Monetary Fund to lend to struggling economies at the G20 London Summit.

A decade on from that panic, we’re seeing stable global growth of nearly 4 percent. Japan and the US are both enjoying their second longest periods of economic expansion in the post-war period. But now I can see new risks on the horizon. There is a possibility of another financial crisis, and its roots may stem from what countries did a decade ago to contain the 2008 global panic.

New Bubbles Emerging with Few Policy Options Left

Historically low interest rates were initially thought to be quick remedies to treat the damage of the Lehman Brothers collapse. But central banks around the world ended up keeping those low interest rate policies in place for a long time. In fact, the Bank of Japan and the European Central Bank still have negative interest rate policies in place. This has created an unusual and difficult situation: we’re close to seeing a bubble in US stock markets, and maybe here in Tokyo, too. Yet, we’re still continuing to pump liquidity into our markets in an effort to boost the economy. We’ve seen capital inflows to emerging economies, and now a quick reversal could trigger another financial crisis. China’s mounting private-sector debt, which originated from the country’s 4 trillion yuan stimulus after the Lehman collapse, is weighing on its economy.

And worst of all, in the event of another crisis, countries will have very few policy options left. They won’t be able to lower their interest rates to pump liquidity into the markets, because rates are already so low. They won’t be able to introduce fiscal stimulus, because they no longer have the money to do so, given their hands are already full with huge fiscal deficits.

Tighter Financial Regulation and the Rise of Market Based Finance

Tightening regulations for financial institutions was another response to the 2008 global financial crisis. The Fed introduced stress tests to determine whether banks can maintain sufficient capital even under adverse economic conditions. The so-called “Volcker rule” was introduced to limit a federally-insured bank’s ability to buy and sell stocks, bonds, and risky derivative instruments for their own accounts in an effort to prevent future bank bailouts. As a result, the banking business became less profitable.

Meanwhile, money flooded into non-banking institutions, such as hedge funds and index funds that promise higher profits. Global investment management institutions have ballooned over the past 10 years, with Blackrock and the Vanguard group now estimated to manage more than 10 trillion dollars in assets. Market-based finance has been on the rise for some time now, prompting experts to warn of the risks of having too much money in too few hands.

Faltering G20

Another potential risk is a lack of international coordination. The Group of 20 Summit played a significant role in addressing the situation in late 2008 and 2009 by pulling both developed and emerging economies together to deal with the crisis. But in recent years, challenges have surfaced, with member countries struggling to reach consensus on certain issues. The decline in multilateralism has gained pace since the advent of the Trump administration, making it harder to combat protectionism.

The question is, are we ready for another financial crisis? We’ve recently seen the possibility of another crisis starting in Argentina and Turkey. Global economic growth may significantly slow with a global trade war. But can countries work together when a recession hits?

Japan will be hosting the G20 Summit in 2019. Leaders and government officials face an uphill battle to ensure the international forum functions as it should. Or they may need to come up with a completely different framework that does the job better.

This year, the Bank of Japan released the minutes of its June 2008 meeting. The documents reveal that Masaaki Shirakawa, the then-BOJ chief, said that “Maybe the worst period of the crisis had passed”. It shows just how difficult it is to foresee a global financial crisis: BOJ officials had little sense of what was to come, just 3 months before the Lehman Brothers collapse.

The next financial crisis may be just around the corner, and instead of putting too much effort into predicting when and how it will happen, we need to consider if we have the necessary firefighting tools to contain and extinguish the fire.