Price rises fail to sprout

Japan's Consumer Price Index, which excludes fresh food, was up 4 percent in December, year-on-year, due to a weakening yen and the global energy shortage. That was a 41-year high.

Hayashi Shoji runs a company that grows bean sprouts, known as moyashi in Japanese. They're a common ingredient in home cooking, partly because they are so affordable, usually going for about 25 cents for 200 grams.

"Retailers tell us a price hike of about 1 cent a bag would be possible," Hayashi says. "But they say 4 cents is too much."

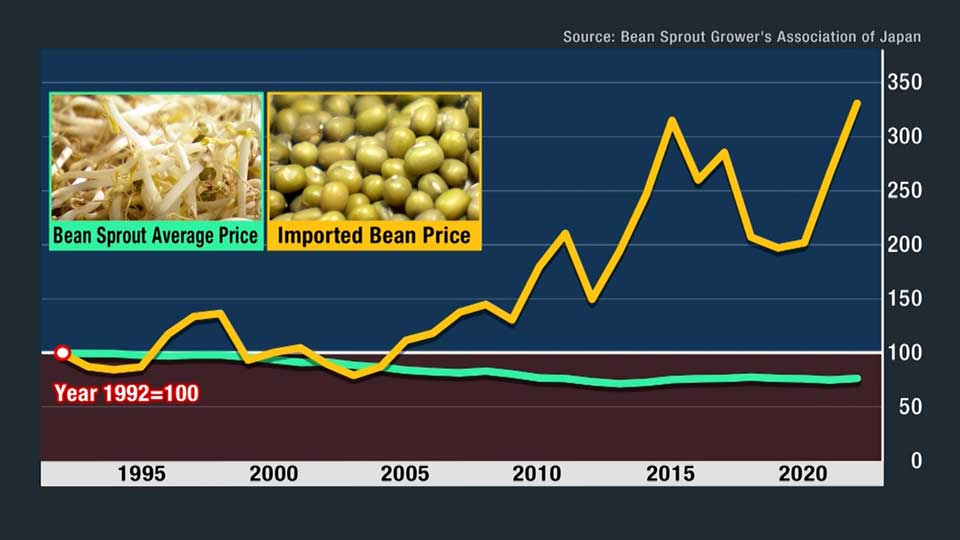

The price of moyashi in real terms has actually fallen over the past 30 years. But the cost to import the beans, most of which come from China, has more than tripled.

Hayashi says the price of beans has risen as China's economy has expanded. He also points out Beijing has been encouraging farmers to grow more high-value produce such as soybeans and corn, reducing harvests of beans needed for moyashi.

The sharp depreciation in the yen last year made imports even more expensive. Hayashi started to look at other possible sources, but quickly realized switching could be problematic. "If we just focused on prices," he says, "we might be able to buy beans from other parts of the world. But we'd like to stick to the Chinese beans because we want to keep producing high-quality sprouts."

Rising energy costs are a further complication, given that the sprouts are grown in a heated space and doused with water warmed to 20 degrees Celsius. Hayashi says the company's electricity bill has doubled and the cost of heating oil is up by 50 percent over the past year or so.

Hayashi has teamed up with other moyashi growers in an effort to get more from retailers. The growers' association ran a full-page newspaper ad to back up their case, claiming "we cannot survive if we keep selling at such low prices." That followed a series of letters to retailers calling for price hikes.

But Hayashi still hasn't got the increase he needs. He says it would take a 20-percent hike to cover his costs, but so far he has only got half of that.

Dilemma for customer-facing businesses

Supermarkets are struggling as well. Akiba Hiromichi manages a small chain of shops in the Tokyo area. He has received countless requests from suppliers to raise prices. He says he has never experienced anything like it, with "both the size of the price rises requested and the number of items affected" being extraordinary.

Akiba is reluctant to pass on all these cost hikes to his customers. His shops did raise the price of milk but he says that has resulted in a razor-thin profit margin, noting that some items are actually sold below cost. He used to stock up on products when a supplier warned of a price hike. But now they are running out of storage space.

"The government thinks it's fine to raise retail prices if wholesale costs go up," he says. "But it's not that easy if you're the one dealing with customers face-to-face."

Call for wage increases meets with uneven response

The Japanese government has been urging companies to give workers higher wages. The goal is to change an entrenched mindset that aims to ringfence corporate profit by keeping a tight rein on wages.

But there has not been a smooth rollout of plus-side inflation driven by wage hikes. Dai-ichi Life Research Institute Senior Economist Hoshino Takuya says "the current inflationary situation is not what the government was aiming to achieve."

In countries such as the US, price hikes are often the result of rising wages. In Japan, however, prices are being pushed up by higher costs.

"The weaker yen has helped export-oriented manufacturers improve their performance so they can raise wages if they decide to do so," Hoshino says. "But small and midsized businesses depending on imports can't even manage to pass on higher costs in their own prices. Raising wages is not an option for them."

With both moyashi growers and grocery store operators feeling the pinch, it is clear that many Japanese firms are being squeezed. Recent signs of a strengthening in the yen have offered little hope of respite, meaning there are likely to be calls for further government efforts to drive up wages in order to offset rising prices.