BOJ maintains yield curve control

Governor Kuroda Haruhiko faced questions in parliament on November 2 about whether the central bank was correct to be going against the global trend. Specifically, lawmakers wanted to know about "yield curve control" (YCC), a policy Japan has been pursuing for the past six years.

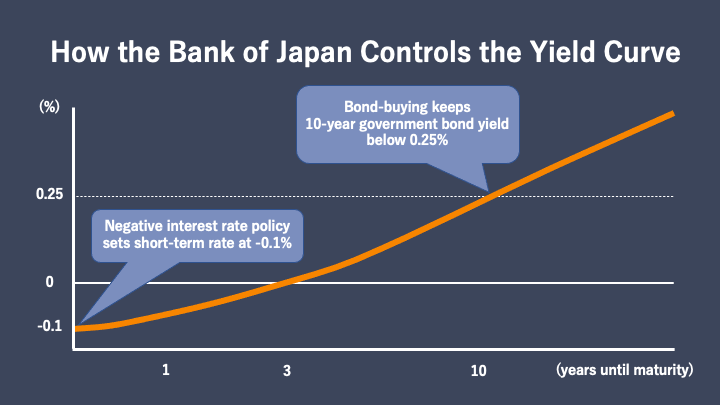

The idea is to spur the economy by keeping interest rates low. YCC targets the long-term rate by pinning the 10-year government bond yield at around 0%. But the yield has been facing upward pressure as rates rise globally, so the BOJ has been buying unlimited amounts of bonds from the market to keep this figure below an upper limit of 0.25%.

As the BOJ's negative interest rate policy sets the short-term rate at -0.1%, a graph depicting yields of various maturities currently forms an upward curve, of sorts. The yield curve is supposed to fluctuate depending on market conditions, but the BOJ has been keeping it roughly within a target range by buying 10-year government bonds.

In parliament, Kuroda said the BOJ could change its approach if Japan can hit -- and maintain -- the Bank's 2% inflation target. He dismissed the idea of implementing changes now.

Economist Musha Ryoji, President of Musha Research, calls yield curve control an "extreme" policy. "Yield curve control is basically a policy that says the central bank will decide long-term rates in addition to short-term rates. This is a policy that almost no country has adopted, and is aggressive even from a monetary easing standpoint," he says.

But he also says YCC was necessary at the time it was introduced. "Japan had been in a prolonged period of deflation," he says. "Against such a serious disease, a powerful drug was needed."

Yield curve control means weaker yen, higher prices

In the United States, meanwhile, the Federal Reserve has been tightening its monetary policy to tame inflation. This has sent Japan's currency crashing to a 32-year low against the dollar, because investments in countries with higher rates promise better returns.

The weaker yen is sending import prices higher, and driving up living costs for the Japanese people.

Pressure for the BOJ to end YCC

Economist Fukumoto Yuuki, a researcher at the NLI Research Institute, says the spiraling cost of living may create pressure for the Bank of Japan to change tack. "If the economy struggles because of higher prices, politicians could lean on the Bank to alter its policy."

BOJ's logic to keep policy ultra-easy

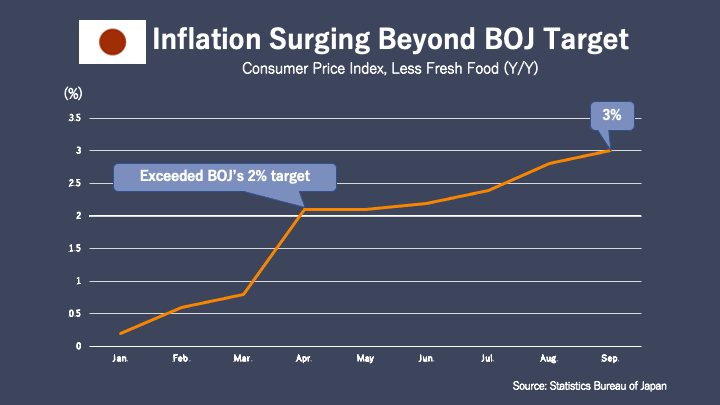

In fact, the key measure of inflation has already passed the 2% mark. The consumer price index (CPI), excluding fresh food, in September jumped 3% from a year earlier.

But Kuroda says this is not a reason to change policy. He says prices are rising because of "the state of the global commodity market and the weaker yen" and suggested these factors will abate in the new year. "I predict the CPI will fall below 2% in 2023," he told lawmakers. "Continuing with monetary easing is still the appropriate policy as we need to realize continuous price stability accompanied by wage growth."

How and when might YCC end?

How and when might the Bank of Japan end its unusual policy?

Musha says that if the BOJ can end YCC on its own terms, meaning amid a strong economy and stable price growth, this would qualify as a "win". The other option is to cave in to public pressure and lift YCC before that, which would constitute a "loss".

Economists suggest a "win" for the BOJ

Musha says his money is on a win for the Bank. He believes the weaker yen will actually work out for the better if the central bank can hold out a bit longer. "The negative effects of the yen are being felt right away. But there's a time lag until the positive effects can be felt," he says.

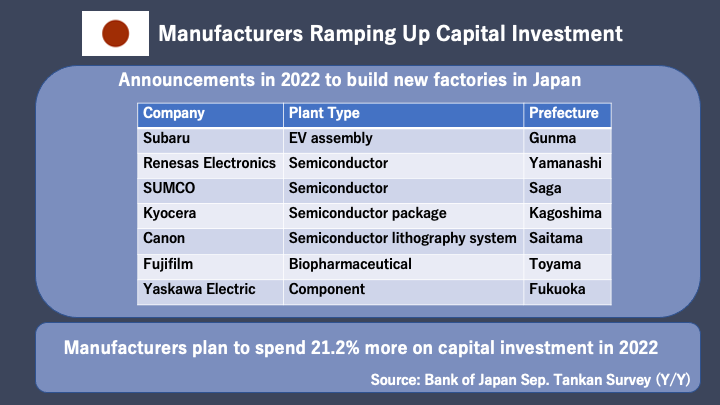

"World demand will soon rush to Japan as its products and services are seen as cheap, thanks to the weaker yen." He notes that, "Manufacturers keep announcing plans to build large-scale plants here... and an index on manufacturers' capital investment plans recently hit an all-time-high."

Musha believes Japan will see a phenomenon called the "J-curve effect" in economics, often used to describe how a country's trade balance initially worsens following a devaluation of its currency, but then quickly recovers to surpass its previous performance. "As Japan enjoys an increase in demand, the country will have a trade surplus, which will offset pressure towards a weaker yen," he says.

Fukumoto holds a similar view. He believes the Bank will be able to hold firm until autumn 2023. "Next year, overseas inflation, which is measured on a year-to-year basis, will ease," he says. "By autumn 2023, price gains overseas will probably have peaked out, leading to a pause in monetary tightening by central banks." Fukumoto believes this would be an ideal time for the BOJ to lift yield curve control as Japan's rates will not face too much upward pressure under such market conditions.

Another reason Fukumoto believes next autumn is the likely timing for change is that the central bank will welcome a new Governor in the spring. "A new Governor may be the catalyst needed for the bank to take another look at its policy," he says.

Surprise Ending

But Fukumoto has one caveat: The central bank won't want investors to see the change coming. "If the BOJ flags its intention to lift YCC in advance, the costs of doing it will balloon." In other words, if investors know Japanese rates are set to rise, they will dump previously issued bonds with lower yields. That could cause Japanese yields to shoot up. As a result, the BOJ would have to keep buying bonds until its cap on yields is lifted. For this reason, Fukumoto says the BOJ will tweak YCC with "no warning." He also notes that if the Bank were to give in to pressure, it might spring a change of course as soon as this year as market participants are not expecting it.

Why the BOJ needs to "win"

Musha says the Bank of Japan simply cannot reverse course under pressure, because people's trust in it as an institution would plummet, and so would market confidence in the yen. "That would lead to a disastrous cycle for the Japanese economy."

Fiscal ace up the sleeve

Musha says the weak yen could prove to be a bonus for Japan's government, and a reason BOJ policymakers won't be spooked into abrupt changes. "The Japanese government owns a lot of assets held in foreign currencies," he explains. "If they were to be sold at a time when the yen is weak, Japan could make 30-50 trillion yen thanks to forex levels. This money could be used to stimulate Japan's economy. Investing in new energy or semiconductor development would be a great way to do that."

While the BOJ tries to stimulate the economy through monetary policy, if the government does play this ace up its sleeve, the Bank may finally get the help it has long awaited from the fiscal side.

A "loss" for the BOJ is risky for the world

What will happen if the BOJ is pressured by the public or politicians to end yield curve control before it has achieved its objective?

This could trigger "a chain reaction of financial panic around the world," according to Musha. He says countries and companies with a lot of debt in foreign currencies could be devastated if a surge in Japanese rates leads to further upward pressure on rates in the US. "The debt burden for those borrowing in dollars would worsen," he says. "Countries and companies with a large amount of external debt could face insolvency."

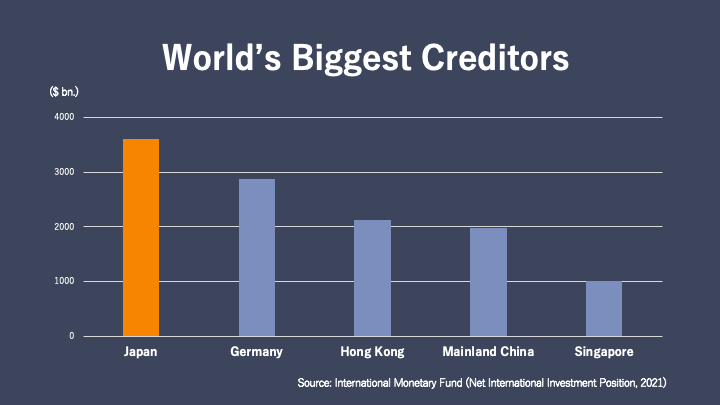

The reason Japan could exert a huge impact on overseas rates is that it owns so much of the world's financial assets. Overseas assets held by Japanese residents at the end of 2021 amounted to 1,249 trillion yen, according to the country's Finance Ministry. In fact, with external assets exceeding liabilities, Japan is the world's largest creditor nation.

"Japan has had low rates for a while," explains Fukumoto, "so, investments in domestic bonds haven't been profitable. Many financial institutions here have been getting returns by holding foreign bonds."

If yield curve control is lifted before overseas rate hikes calm down, Fukumoto says it would have a strong upward pressure on rates in Japan. "Many Japanese financial institutions will see their domestic bonds lose value." This is because bond prices and yields have an inverse relationship.

The effects of an early lifting could impact rates overseas. "When certain investments turn sour, traders tend to sell other profitable investments to make up for that loss," explains Fukumoto. "As the yen has drastically weakened, many Japanese investors have seen their overseas bond holdings gain value in yen terms. If they start unloading such foreign assets, rates overseas may jump." This would further contribute to the already surging rates overseas.

No more easing

Investors may want to brace for the possibility of a global catastrophe whether the BOJ ends YCC with a "win" or a "loss." Fukumoto says, "If Japan turns toward tightening policy at a time when the rest of the world was already doing so, that means no large central bank will be providing the markets with cash. That opens the door to asset prices falling around the world. In the worst case, I wouldn't rule out a financial crisis."

The question of how and when Kuroda's yield curve policy is lifted will occupy economists in Japan and abroad for some time.