Fed rate hikes trigger global reaction

The US Federal Reserve raised its key interest rate by 0.75 percentage point at its monetary policy meeting on June 14-15, bringing the target range for the federal funds rate to 1.5-1.75%. It is the biggest increase since 1994.

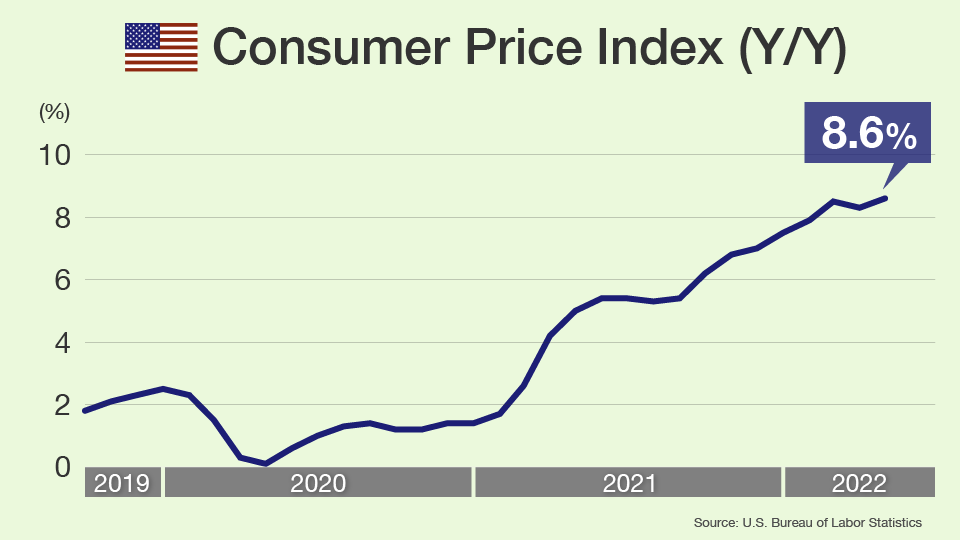

The central bank aims to slow inflation. The May consumer price index in the US was the highest in more than four decades with food and energy costs pushing the rate to 8.6%.

The rate rise is having a global effect, from higher borrowing costs in the US to capital outflows from emerging economies. In Japan, regional banks are seeing their investments in overseas assets sour.

Japanese regional banks suffering unrealized losses

Kirayaka Bank in Yamagata Prefecture is under strain. Its directors have watched its financial position tighten and plan to apply for public money under a pandemic-support program. Representative director Kawagoe Koji says the bank needs to look after itself so it can continue to service customers: "In order to financially support small local firms struggling amid the coronavirus pandemic and take on even more risky loans, we need to strengthen our own financials."

Kirayaka is among about 100 small banks in Japan that conduct the majority of their operations within the immediate geographical region where they are based. They serve as the primary financial system for many local enterprises and their presence has become increasingly important amid the pandemic.

Relaxed conditions for bank support

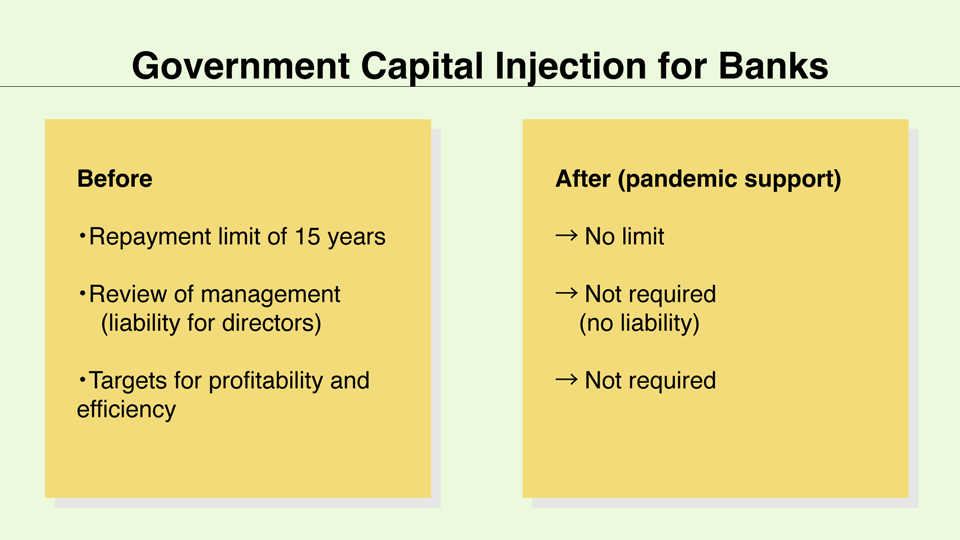

The terms of the Japanese government's pandemic-support loan are attractive: unlimited time to repay taxpayer money and no liability for directors.

The conditions aim to prevent a credit crunch. Kato Izuru, chief economist at Totan Research, explains: "Financial institutions short on cash tend to cut back on loans. When lending money, banks think about the possibility of the borrower going bankrupt and defaulting on the loan. Lenders can be more lenient in their decision-making when they have a lot of capital."

If Kirayaka Bank makes a successful application, it will become the first regional bank to take advantage of the new conditions.

Fed hikes leading to tumble in foreign bond prices

One reason Kirayaka Bank needs help recapitalizing may be its investments in foreign bonds, which fell in value after the US Federal Reserve began raising its key interest rate.

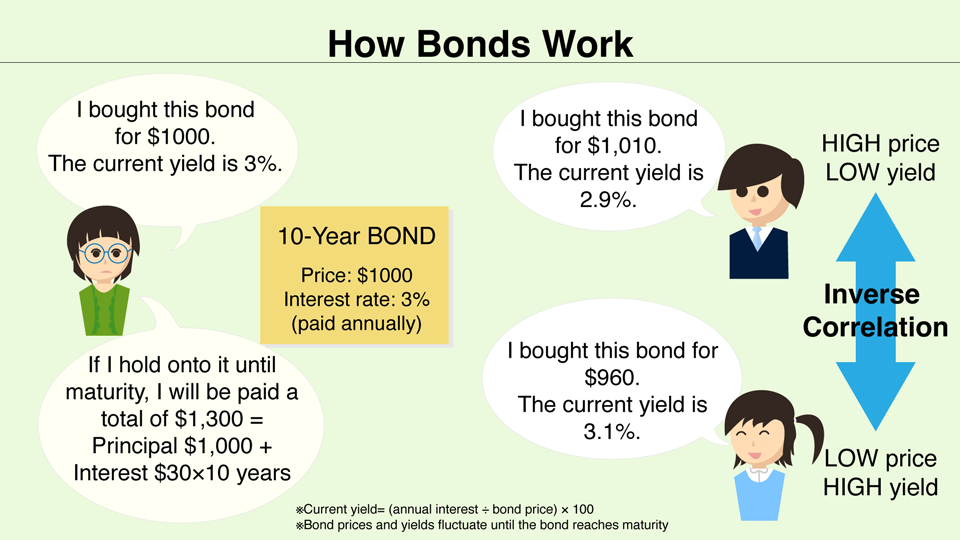

Most bonds are issued with a fixed interest rate, paid when the bonds reach maturity. Bonds are, in simple terms, loans; the issuer is the borrower, while investors take on the role of the lender. The annual profit investors earn on the bond is called yield. When rates rise, previously issued bonds with interest rates fixed at lower levels become less attractive to investors. Thus, investors tend to sell the old bonds and their prices fall, while their yields rise. Generally speaking, bond prices and yields have an inverse relationship.

Ito Shoichi, senior managing director at Nagomi Capital, explains how bank balance sheets are impacted: "If market rates now are higher than the rates on the bonds you've already bought, those assets turn into unrealized losses." An unrealized loss is a devaluation of assets on paper. It results from holding an asset that has decreased in price; if it is yet to be sold, the loss is not realized.

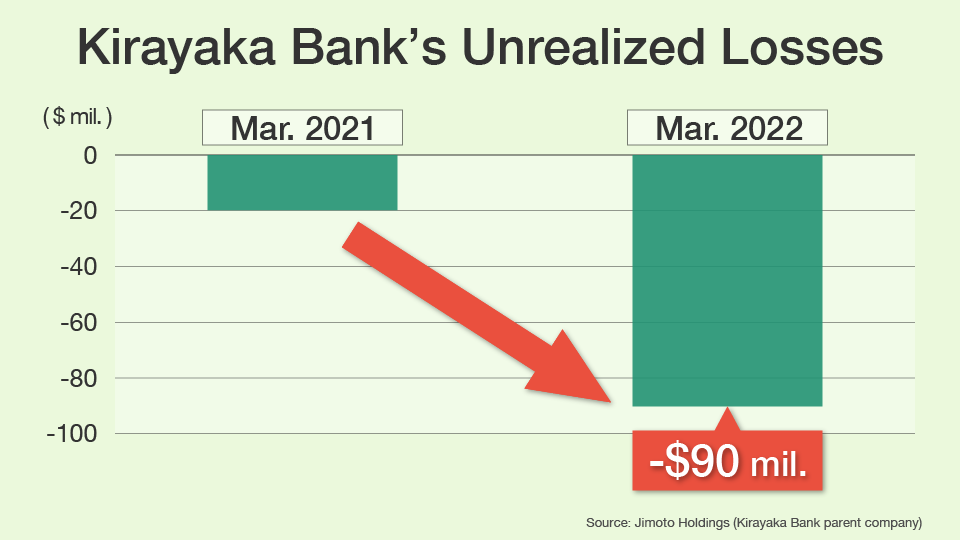

Kirayaka Bank's paper losses ballooned to about 90 million dollars (12.1 billion yen) in March 2022. That's more than quadruple the amount the previous year.

Kirayaka Bank isn't the only regional bank facing problems. Shibata Hisashi, chairman of the Regional Banks Association of Japan, thinks the current environment makes asset management difficult. "Of the 59 regional banks in our association, all of them have seen the value of their investments decline. They've lost about $11 billion (1.4 trillion yen) combined in one year. This means regional banks have lost about 30% of their investment profits on average. Managing portfolios as overseas rates surge is extremely challenging."

BOJ easing made regional banks look overseas

Japanese regional banks have been buying up foreign bonds over the last decade. Kato says the trend was driven by the Bank of Japan's ultra-easy monetary policy, which began in 2013. "Japanese banks used to profit from two types of interest payments. The first was loans. The second was investments, mainly into domestic bonds. However, because the Bank of Japan lowered rates in Japan, financial institutions could no longer profit in the same way."

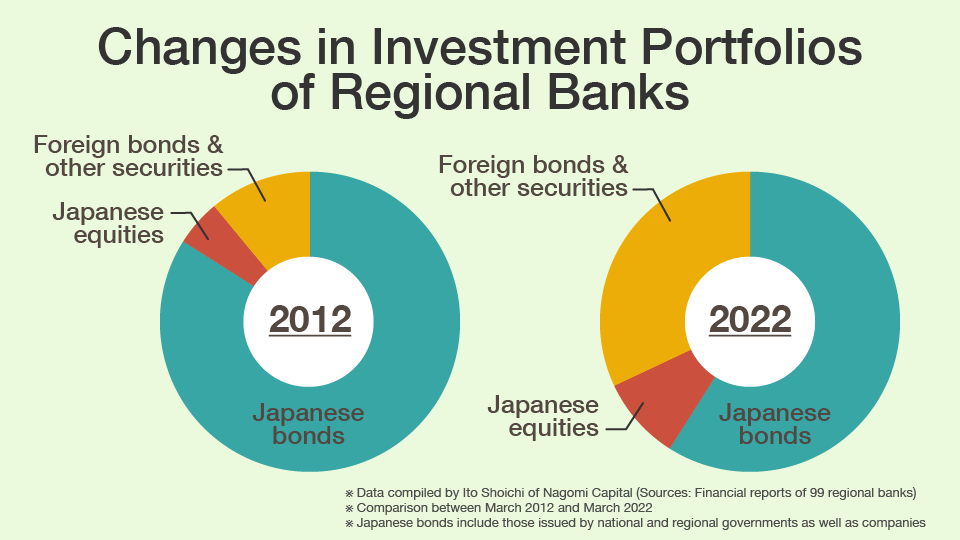

As profiting in Japan became difficult, regional banks sought higher returns overseas. Ito explains: "Countries outside of Japan, such as the United States, had higher interest rates, so regional banks increased their investment in foreign bonds as the BOJ kept rates in Japan low." Investment portfolios of regional banks changed: "A decade ago, 80% of the assets they managed were bonds in yen, but that figure has fallen to 60%. Foreign bonds and trusts used to account for only 10%, but have jumped to over 30% in recent years."

Implications of unrealized losses

Experts predict several possible repercussions for regional banks with unrealized losses.

Actual losses

The types of overseas bonds held may determine whether the losses are realized. "If regional banks are invested in bonds that are relatively safe, like those issued by stable governments, they will make their money back if they just hold on until their bonds reach maturity," explains Ito. "But if they own high-risk bonds, the issuer might default before the bonds reach maturity."

Investment portfolios differ between banks. At Kirayaka, Kawagoe argues that its investments are not a problem long-term. "Our unrealized losses are mainly from overseas bonds. Most of them have very low default risk, such as US treasury bonds or Canadian ones. If we hold them until maturity, the unrealized losses can be improved."

Kato supports the argument, pointing out that "if the assets are not sold, the paper losses will not be realized, so holding the bonds until maturity is one way to cope."

Limited means to profit

Unrealized losses do impact banks' bottom lines as they affect overall strategy. Kato says they "limit the scope of asset management". "Higher interest means that if you buy new bonds, you will earn more on them, so in essence, portfolio managers should want to ramp up purchases of foreign bonds. But if they're forced to hold the previously issued bonds until maturity, they will not have much leeway to make new investments."

Kirayaka Bank is aware of the tight spot it's in. Kawagoe says the institution wants to improve its financial situation in a short period of time, "so we are thinking of changing positions."

Less incentive to lend

Small business in Japan could find itself at a disadvantage if regional banks are less open to offering loans. "Regional banks incurring losses from US bonds will have difficulty lending to local firms," warns Kato. "When contemplating loans, financial institutions have to consider if borrower might go bankrupt and default. Banks will find it easier to take risks when they themselves are financially stable."

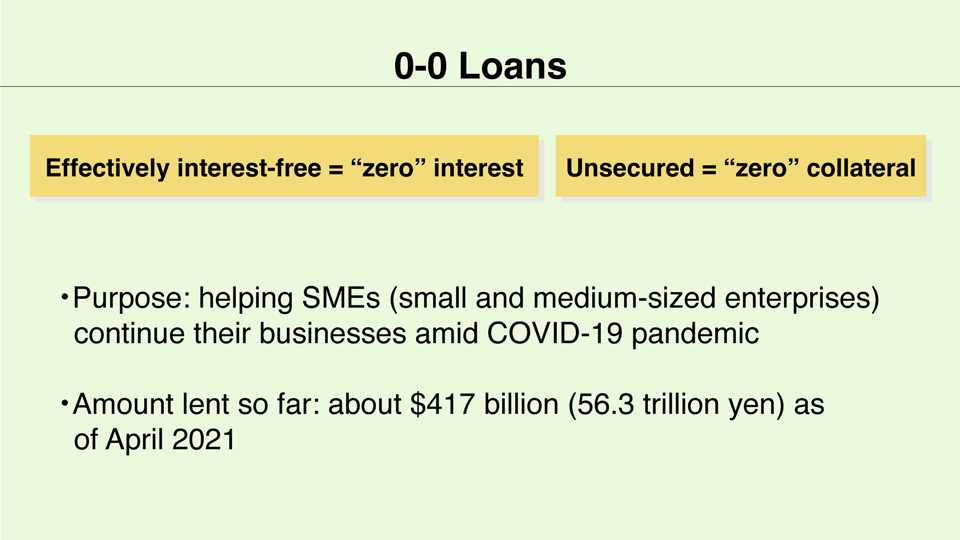

Bank lending is set to become a bigger issue in the near future, according to Ito. He says pandemic-support financing taken out by many local companies known as "0-0 loans" will be key. This lending allowed firms struggling amid the pandemic to borrow money with zero interest and zero collateral, hence its nickname. "Many borrowers will soon be required to start paying back their loans, but with Japan still not back to pre-pandemic levels in many parts of society, some may not be able to do so," notes Ito. "This will mean more credit costs for their lenders. Regional banks with profits from their investments might be able to cover the added costs and still grant new loans, but those with little profits will not be able to do so."

Too much protection will hinder growth

A credit crunch might be avoided if strained regional banks all shored up their financials through the available public funds. But too much protection on both sides could be a problem in the long run. "The number of companies going bankrupt now is very small, rivaling the figure for when the Japanese economy was booming in the early 90s," says Kato. "Less bankruptcy is a good thing if it's due to a strong economy, but when it's just due to clever financing, it leads to bad metabolism in the economy. When Japan readies a safety net, it tends to keep it in place. If weak companies keep operating, that hinders overall growth."

The Japanese government is protecting regional banks, and they, in turn, are propping up local companies. But if they keep that up for too long, it could do more harm than good.

Future of Japan's regional banks

While government loans will guarantee the short-term future for regional banks, their longevity depends on how they manage three key risk areas: currency fluctuations, the domestic bond market and their own business models.

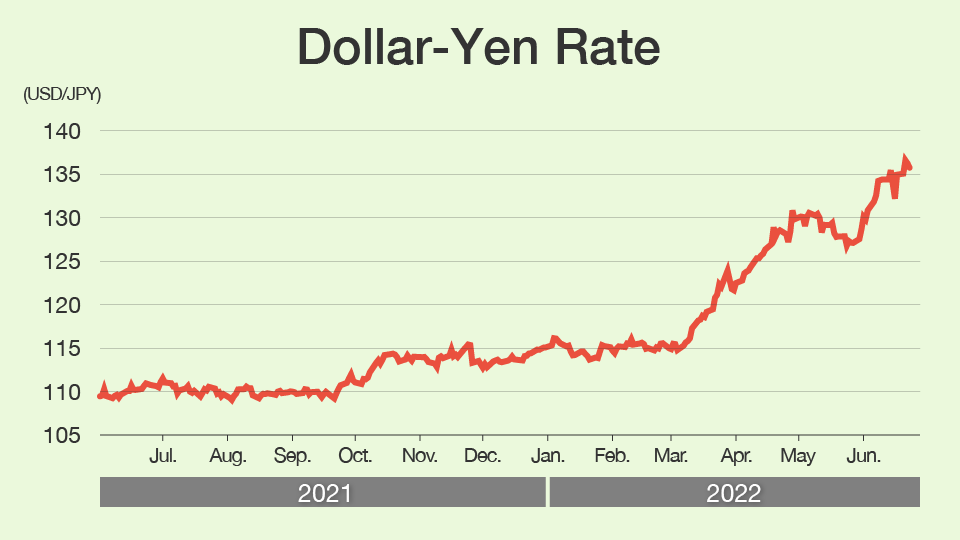

Weaker yen may add to losses

When Japanese financial institutions invest overseas, their profits and losses are swayed by the strength of the yen. The yen has been weakening as the US Federal Reserve tightens policy while the BOJ sticks to monetary easing. This means that even if newly issued foreign bonds promise healthy returns due to higher interest rates, they do not make good investments for Japanese regional banks because overseas assets in yen has become pricier. "If the cost of acquiring the dollar is taken into account, regional banks may see their potential profits suffer," warns Ito.

Further risk from domestic bonds

Another potential stumbling block is Japanese bonds. "Although regional banks have been decreasing their investments into domestic bonds, yen-based treasuries are still the primary asset they hold," explains Ito. The main reason Japanese bonds aren't seeing prices tumble like their American counterparts is that the BOJ has been supporting their value through unlimited bond buying. This is a part of its ultra-easy monetary policy; bond buying keeps long-term interest rates low. However, yields on 10-year government bonds briefly went over the BOJ limit of 0.25% in mid-June. Whether the BOJ can keep controlling bond yields and prices may determine whether there will be further unrealized losses for regional banks.

Reinvention needed to thrive

From monetary policies to depopulation, many of the conditions that affect regional banks are out of their control. In order for them to thrive in the future, reinvention may be needed. "Regional banks will need to do more than just manage the assets that are deposited to them. Advisory work may be one solution," says Kato. He adds that local communities need to change as well too: "If society can be digitalized, it could offer opportunities for companies in rural prefectures." By being a part of community-level progress, regional banks can ensure their relevance and profitability.