Joseph (not his real name) has endured considerable hardship to get to where he is today. He still has a giant bureaucratic hurdle standing in his way, but in the meantime has worked to establish a Japan-based NGO that will support medical care in his home country.

He is waiting on an outcome for his second refugee application after his first bid was rejected. But he has come a long way since landing in Japan in 2018 knowing no one and with less than $200 in his pocket.

Joseph has earned a master's degree at the Kanagawa University of Human Services Graduate School of Health Innovation. "This is a new beginning for me," he said at the graduation event. "I am very happy because having this diploma is going to allow me to contribute to Japanese society and the world."

The course he completed is designed to help professionals become global innovators in healthcare and welfare. Participants conduct research activities in areas relevant to Japan to help manage urgent issues such as its aging society.

Joseph was born in the east of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, an area known for violent atrocities committed by armed groups. The eldest of many children, he made his way to medical school and graduated from university.

His concern about continuing insecurity and inefficient government policies prompted him to form a political group with several hundred members in 2013. Joseph accepted a job as a public officer that necessitated a move to the capital, Kinshasa. He settled, got married and had a baby, and carried on with his political activities.

But young political activists of his generation began to disappear. Joseph started receiving threatening telephone calls. Government police came knocking at his home on two occasions and Joseph feared arrest.

Passage to Japan

He used his official passport to flee, leaving his wife and child behind. He bought a ticket to Japan, a country he believed was safe and less discriminatory against African people than other destinations.

Joseph arrived in June 2018. He spoke no Japanese or English. The day after he landed, he applied for refugee status with the help of the Japan Association for Refugees in Tokyo.

As money ran out, he spent nights at a fast-food restaurant. During the day he slept in a corner of the association's office. Joseph received food and clothes from the Catholic Tokyo International Center (CTIC).

While awaiting an outcome on his refugee application, he decided it was essential he learned to speak Japanese. He signed up for classes that were paid for by the CTIC and took a night-time delivery job. "I slept little and kept receiving messages from other Congolese in Japan saying: 'It's useless to go to school. You should earn more money. I can introduce you to work at construction sites.' But I didn't quit my language class."

To practice Japanese, he befriended some university students who visited the CITC. They offered him some share house accommodation in central Tokyo where he lived for eight months.

The students were active in an association called WELgee, a group that helps asylum seekers be more connected with society. Joseph began to share his story at speaking events.

A helping hand

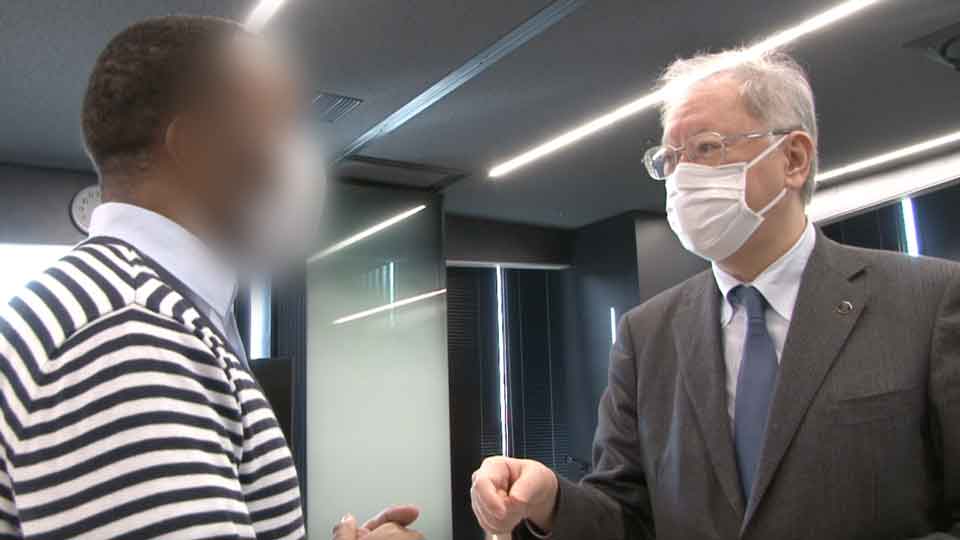

Through WELgee, Joseph was introduced to Shuto Kenji, the vice-governor of Kanagawa prefecture who is also a doctor by training. Shuto had dreamed in the past of working in Africa as a medical doctor and was impressed by Joseph's tenacity.

Without a Japanese medical license, Joseph is unable to practice in Japan. He told Shuto about his interest in further education and helping to support Japanese medical activities in Africa. That was music to Shuto's ears.

Shuto took Joseph under his wing: "Through him, I remembered the dream of my youth. But it's about more than that when you see how much passion and thoughtfulness, he has despite the hardships he has endured. I think everyone would want to support him."

Shuto introduced Joseph to the graduate School of Health Innovation and advanced him money to cover the fees. The school accepted progressive payment for tuition and Shuto found Joseph a job at a major hospital in Kamakura city assisting foreign patients.

"It was a big change delivering me from labor work and total uncertainty," says Joseph. "I had absolutely no idea when the Japanese government will answer my claim as a refugee. It is so hard to be accepted. But at least with a Japanese education, I knew I would not end up with nothing."

He was able to find budget lodging at the nearby Arrupe Refugee Center which had just opened under the direction of a former CTIC director he knew.

Still waiting for a determination on his refugee status and having to renew his temporary visa every six months, Joseph managed to find his way with his studies, employment, and lodging. He worked by day and studied at night.

Building a bridge between Japan and Congo

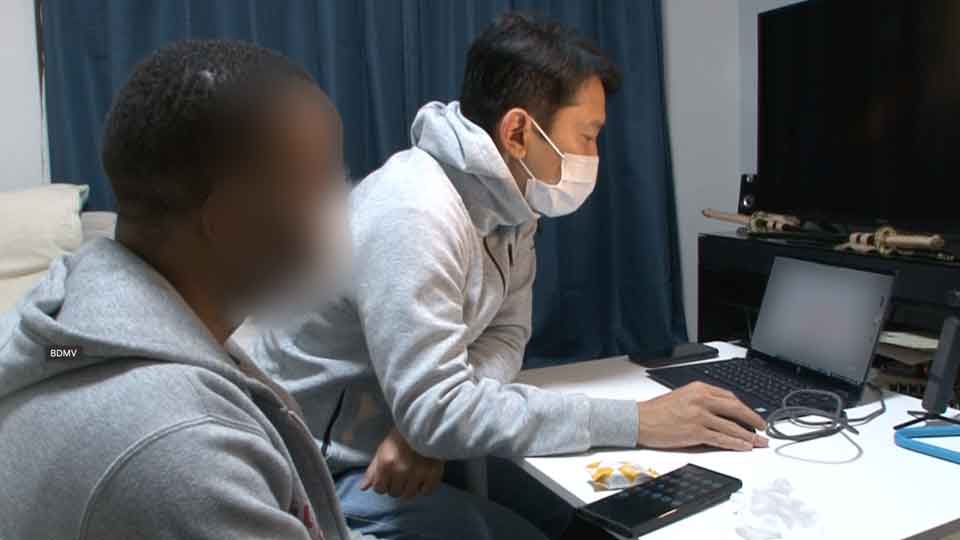

At work, he was approached by Ebisawa Kenta, a manager who shared Joseph's interest in helping to provide medical care in Africa. The pair became friends and, together, in 2021, created a non-profit organization that connects Japanese professionals with doctors and universities in Congo.

The group provides education to Congolese students and professionals using a web conference system. They currently hold weekly lectures. And while the organization is new and is struggling for the funds it needs to provide students in Congo with computers and access to the internet, Joseph is full of hope.

Beside the lectures, he has online meetups every Friday night with Congolese students to discuss their goals and what lies ahead: "There is so much energy. I would like to bring some of these students to study in Japan," he says.

"Joseph is one of those people who makes you feel instinctively that you want to share his dream and enjoy the journey together. That is his true power," says Shuto.

A bureaucratic blow

In the meantime, Joseph waits patiently for official acceptance. He has had to make continual applications to renew his temporary visa. "You worry about when it will expire all the time and can't live a positive life," he says.

In December 2020, Joseph's initial refugee application was rejected. That came as a shock for him and his many supporters. Ebisawa and his colleagues rushed to help and found themselves surprised to learn about the low 0.5% rate of refugee status acceptance in Japan. They were also concerned that Joseph could end up in detention if his visa was not renewed.

With the help of his employer and WELgee's legal specialist, Joseph applied for a regular one-year working visa as an Engineer/Specialist in Humanities/International Services. It was a complex process but he was finally granted the visa last year.

"I feel I had been constantly living in the clutches of the Immigration Bureau so it was a relief," Joseph says. But he insists he is a refugee and wants to be recognized as one. He has lodged a second application and is awaiting an outcome.

Joseph now gives advice to other asylum seekers through WELgee. "Everything is connected in Japanese society," he says. "I trust that with hard work, respecting the rules and co-operating with people, the dots can somehow connect."

Joseph is still seeking ways to be reunited with his wife and child he has not seen for four years. The bureaucratic process could take years, meaning he will miss out on watching his child grow. That heartache comes as he builds a bridge between the medical system of Japan and Congo, forging links and winning support.

NHK is not revealing Joseph's real name due to fears for the safety of his family in DR Congo.