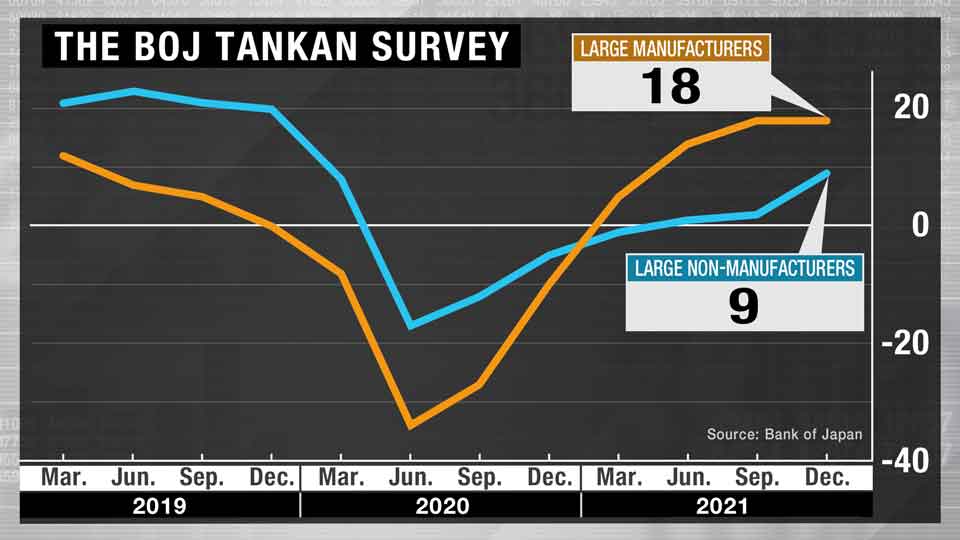

Every quarter, officials at the Bank of Japan ask companies throughout the manufacturing and non-manufacturing sectors how they feel about the state of business. The most recent Tankan survey turned up some promising results.

It showed that hotels, restaurants, amusement parks and other large non-manufacturers are feeling more upbeat than at any time since December 2019, just before the start of the pandemic.

Large manufacturers are also positive on the whole, but with no improvement in sentiment from the previous survey. One factor weighing on confidence across this sector is stubbornly high prices for energy and materials, a result of surging demand, geopolitical tensions, and efforts to address climate change. Another is supply chain disruptions. And yet another is the threat to exports from potential slowdowns in China and Europe.

As encouraging as the overall results of the survey appear, economists say they should be treated with caution. They note the poll was mostly conducted before the emergence of the omicron coronavirus variant, which could temper optimism in the months ahead.

Moreover, they are outright rejecting predictions from earlier in the year that Japan’s GDP might return to pre-pandemic levels in the final quarter of 2021. For that to happen, the economy would need to expand at an annualized rate of 9.5 percent between October and December. The latest consensus is that growth will be closer to 6.5 percent. Economists project that the second quarter of 2022 is the earliest that Japan will get back to the kind of figures it was seeing in 2019.

Prime Minister Fumio Kishida is aiming to help the economy get there with a $490-billion stimulus that includes cash payments for families with children and struggling businesses. It also earmarks funds for the domestic semi-conductor sector—part of an initiative to build a more resilient supply chain.

As comprehensive as the package looks, it may not be enough to convince consumers. Electricity bills and gasoline prices continue to rise. Prices for basic food items such as soy sauce, mayonnaise and beef are also going up.

Inflation may even temporarily hit 2 percent in 2022. That may not sound particularly high to people living in countries such as Britain and the US, where inflation has shot up past 5 percent this year, but for Japanese consumers used to chronically low price increases, it will come as a shock.

Kishida says companies can do their bit to help people prepare. He wants them to raise wages next spring by more than 3 percent, ensuring what the government calls a virtuous cycle of distribution and growth.

There are already some early signs that an economic recovery may be coming. The semiconductor shortage is starting to ease, and car exports are picking up. The challenge is now for the government and businesses to build on these improvements, by giving consumers the confidence to go out and spend.