COVAX, a multi-agency project, stands for COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access. It aims to ensure fair distribution of the vaccines, particularly to lower-income nations, and was initiated by several organizations, including the WHO and UNICEF. Under the program, 33 million doses had been delivered to 74 countries and regions as of April 1. But reaching the people it wants to help is proving difficult.

Lebanon is a case in point. On March 24, it received 33,600 AstraZeneca vaccine doses courtesy of COVAX. The country has recorded over 460,000 infections and more than 40 people are dying every day. An economic crisis – worsened by a devastating explosion in Beirut last year – has plunged many into poverty and despair.

The UNICEF Lebanon representative, Mokuo Yukie, expects many issues to arise as the COVAX vaccinations are distributed.

“While the main focus tends to be on the vaccines, it’s not just the vaccines that are important,” she says. “UNICEF has secured other items, including syringes, face masks for protection against the coronavirus, and hygiene products for cleaning. There are worries that the situation will be chaotic until everyone gets vaccinated.”

Reaching refugees

The vaccine drive is complicated by the fact that Lebanon hosts a sizable refugee population, including an estimated 1.5 million people from neighboring Syria. The country has the biggest refugee-to-population ratio in the world. UNICEF has worked with the Lebanese government to ensure that eligible refugees are included among the high-risk groups that get vaccine priority.

So far, very few refugees seem to know about the shot. According to the country’s public health ministry, less than 2 percent of the refugee population had registered for it.

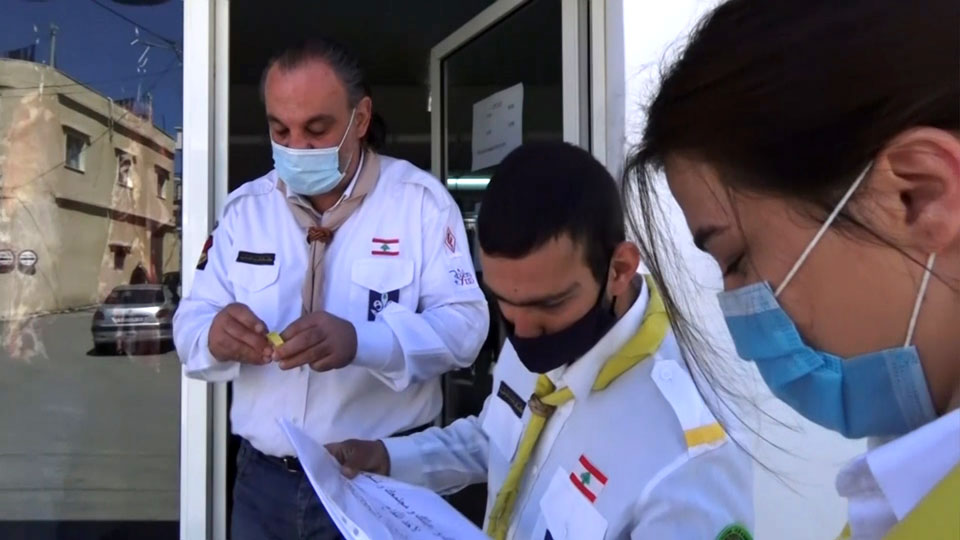

In the eastern region of Ablah, an area with a large refugee population, many residents are unaware that a registration system even exists, despite efforts by local officials. Most people don’t even wear face masks. The area’s COVID-19 Response Coordinator, Reema Semaan, says many refugees don’t appreciate how serious the coronavirus is.

“They believe COVID-19 is just a common cold that will eventually heal,” she says. “People need to first and foremost be informed that it is harmful enough to cause death.”

UNICEF Communication for Development officer, Yotsui Mihoko, says the low registration rates in the country are linked to Lebanon’s financial problems.

“The economic and political situation is so bad that many are struggling just to make ends meet,” she says. “As the nation’s poverty rate has increased from about 20 percent to 50, people are more concerned about how to stay afloat than getting vaccinated.”

The dire economic conditions have contributed to a growing distrust of the government. Lawmakers made it worse when they and some of their staff jumped the line and took the vaccines in February. The president, his wife and members of his entourage, were inoculated too. That brought a strong rebuke from the World Bank, which had agreed to finance $34 million to the country’s vaccine program on the understanding that the early doses should go to the most vulnerable. The Bank threatened to suspend its financing.

Misinformation and distrust

Fake news is also affecting attitudes toward the vaccine. Some social media posts pretending to come from UNICEF claim that drinking hot water and sunbathing can prevent infection.

UNICEF’s Mokuo Yukie warns that it is easier for disinformation to spread in impoverished societies. She says it is crucial to provide reliable facts.

Some people are citing religious reasons for staying away from the vaccine. Worries that the shots have not received Halal authentication - certifying they were made in accordance with Islamic requirements – appear to be growing. While the WHO Advisory Committee has confirmed that a vaccine produced by Johnson & Johnson is halal, it has not offered any such assurances for the AstraZeneca shot which COVAX sent to Lebanon.

Despite these challenges, Lebanon’s government plans to vaccinate 35 percent of the population by the end of the year. And to achieve this goal, Mokuo says COVAX’s work to ensure equitable access to the shot will be crucial.

“The vaccine must be given fairly, regardless of race, social status, or religious background.”