A 74-year-old woman with stage-four pancreatic cancer moved home earlier this month to live out her remaining days surrounded by loved ones. She says she feels “more at peace now than ever at home."

Her family wanted her in the hospital where she could get faster emergency treatment. Then the coronavirus forced the hospital to stop allowing more than one visitor a day.

Her daughter said: "We all wanted to go see her at the hospital and hold her hands. But because of the coronavirus, we couldn't do anything like that."

Tanaka Kimitaka is a home care doctor. Since Japan’s coronavirus outbreak began, he says many families have made similar decisions.

For terminal cancer patients, Tanaka needs to check on them frequently because their conditions change suddenly. Since he has more of these patients, he has more people to visit in one day. He had to visit 17 homes and nursing facilities in a single day earlier this month, about twice the number he usually sees.

It is not just his work that’s changing. In Japan, many rehabilitation programs and nursing services have been canceled for over a month. Some facilities have closed permanently due to the pandemic.

Tanaka is concerned that if his patients go without this help for long, it will affect their overall health and lifestyles in a domino effect.

"The longer these elderly patients stay in their beds, the more they are likely to take fluid into their lungs and get pneumonia, or fall and break their limbs,” Tanaka said. “Eventually, they’ll end up needing more support to maintain their daily lives."

Tanaka says there needs to be a balance between providing medical care and protecting patients from the virus. Home care doctors don’t have access to the same protective equipment they would have in hospitals.

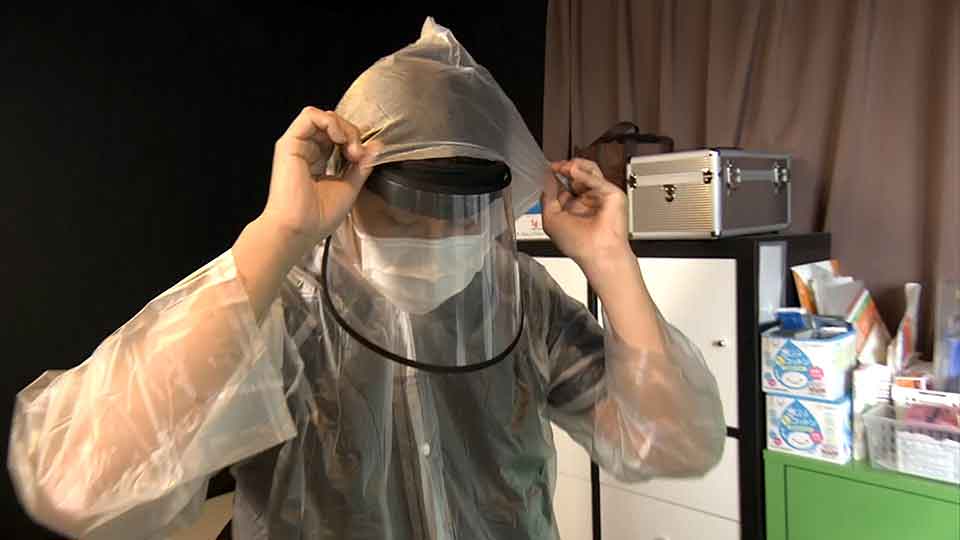

If a patient gets a sudden fever, Tanaka pulls out gear he made out of a raincoat. But he worries whether these measures are enough to protect him and his patients.

"Home care doctors are asking each other what kind of measures or decisions they made to contain the spread of virus,” Tanaka said. I feel like preventing the spread relied heavily on each doctor's decisions, which isn't safe because we are not experts in infectious diseases."

The Japanese Association for Home Care Medicine, a group that represents home care professionals, conducted a survey in March. Many doctors and nurses raised concerns that they don't know what measures to take to protect their patients and themselves.

Ishigaki Yasunori, the vice president of the association, says the government is only concerned about taking measures for hospitals.

"I think it is the role of the government and the administration to come up with standards for how to deal with a virus we’ve never encountered before," he says. He adds that the association plans to ask the government to create guidelines for home care medical staff.

As the virus continues to pose new challenges, doctors like Tanaka hope they’ll have the tools they need to keep their patients and themselves safe.